Photo by Beth Macdonald on Unsplash

Keep Calm and train a settle

Settle is one of the most misunderstood dog training exercises out there, which is a shame as it’s one of the most important skills to teach your dog if you intend to include them in your life outside of the home.

Increasingly, students come to class or private lessons looking to teach their dog to relax at the patio, office, camping or visiting with friends. When describing their dogs in these settings, they’ll say “He can’t sit still, he’s always checking things out”, “She looks right at me and barks”, and most tellingly “My dog seems to get frustrated if they have to sit still for any length of time”.

Sometimes pet parents notice their dog is struggling with nipping, mouthing, humping, jumping and other high-arousal behaviours, and seek to teach settle as a quick fix to these issues. Teaching settle can help tremendously with hyper-arousal issues over time, but expecting a nascent settle cue to override big feelings is an exercise in bitter disappointment. A nuanced understanding is required for success here. Luckily for you, you’re reading my blog. We eat nuance for breakfast.

Settle vs. Stay (and how treats have betrayed you)

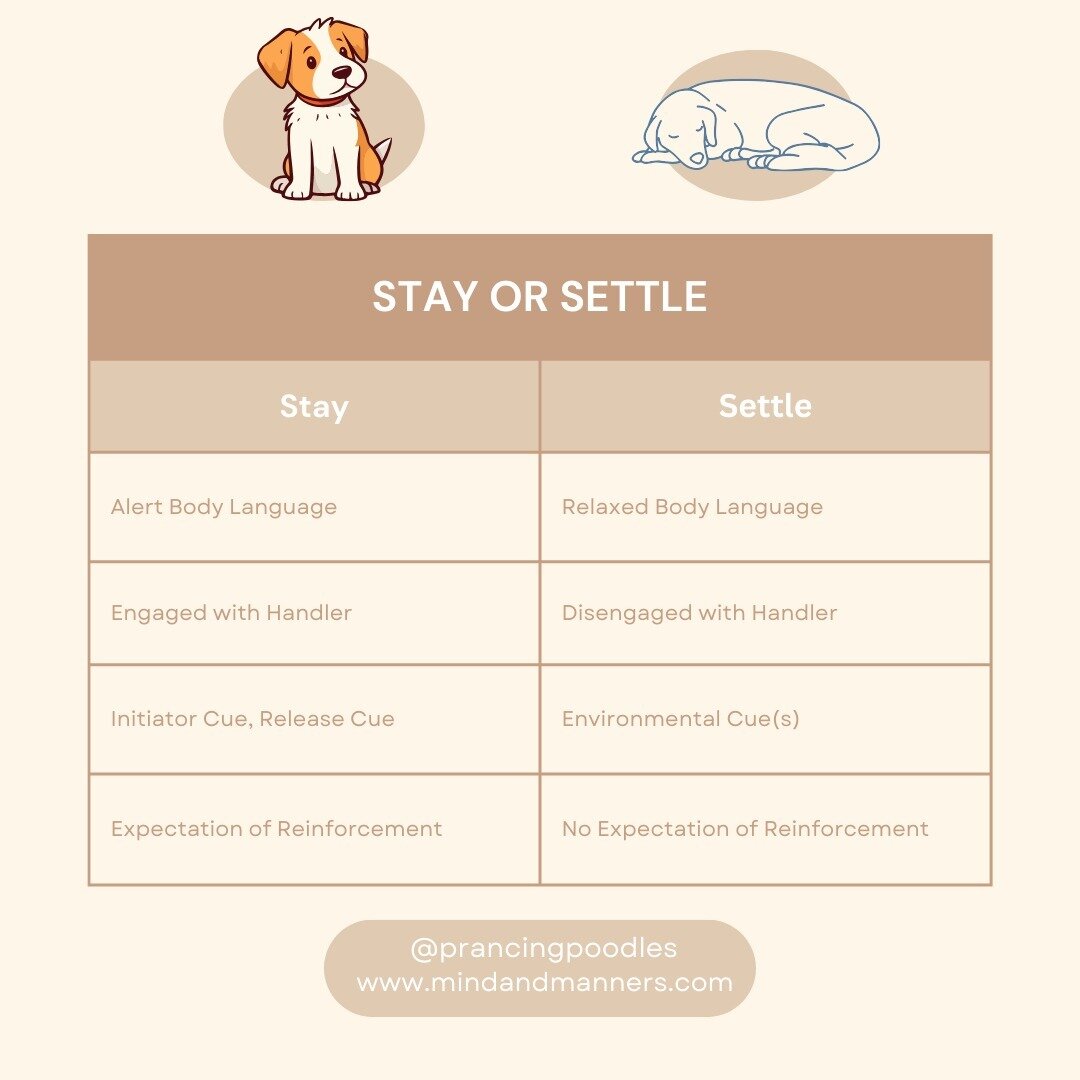

A settle is not a stay. Say it with me now, louder: a settle is not a stay. These two exercises often get mashed up, leading to confusion and frustration in both dog and handler.

A stay is an obedience exercise where the dog maintains a defined position for a defined period of time. A stay starts and ends with a cue from the handler, and typically lasts no longer than a few minutes. While the dog is holding a stay they are actively waiting for the second cue, the release cue, to break position. During a stay, I expect my dog to be fully engaged with the exercise and ready to spring into action at any moment. For my dog’s part, they are expecting to be reinforced for a job well done.

A settle, on the other hand, is not an obedience exercise at all. We are looking for a dog who is relaxed and calm, disengaged from activity. We don’t mind if they’re sleeping on their side or sitting quietly, and it’s OK for them to get up to drink water or stretch. We don’t expect them to maintain eye contact, or be ready to move at a moments notice. In fact, they don’t have to engage with us at all - that’s kind of the point, really. All we want is for them to curl up and relax within a defined area for a decent length of time. Usually, I train my dogs to settle on a mat, but you might be working on settling in a crate, on a leash tether, in a car or some other specific scenario which becomes an environmental cue.

Here’s a handy chart to help summarize the key differences:

I want to stress this point here because in my opinion, separating these two exercises is the key to gaining success with either. Most of the time, people train an obedience stay and then hope very hard that it will turn into a settle, despite the dog’s mental state being polar opposites during the two exercises. While I’m sure we’ve all included it at one point or another, “cross your fingers and hope really hard” should not be a step on your training program.

When we train a long-duration obedience stay with positive reinforcement and expect a settle, it almost always backfires. This is because the dog is waiting for a release cue (and reinforcement) that never comes. This process is called “extinction”, and it’s very frustrating for dogs. Dogs who feel like they are doing a good job and are not being adequately reinforced as per previously established expectations will voice their feelings and may even enter a state of hyperarousal (nipping, jumping, whining, mounting). You don’t have to be a dog training genius to see the problem here: extinction is completely incompatible with our settle training goals. Worse still, because extinction behaviours are straight up annoying, we tend to “give in” to our dog’s demand behaviours and deliver the reinforcement as per the old rules of the obedience stay. Now you’re stuck in a loop, where instead of having a nice disengaged settle you have a mat-stay game where your dog holds your attention (and treatpouch) hostage. It would be really funny, if it wasn’t so tragic.

The problem is the reinforcement itself. Food and toy-play, the favoured tools of the modern dog trainer have betrayed us by their very nature - they are just too exciting. Excitement and the anticipation of reinforcement are at odds with a calm, relaxed state we are shooting for. Training a settle with direct positive reinforcement was an uphill battle from the start.

hOW TO tRAIN A sETTLE, method 1: Desensitization

Eleanor, 15 months, settling on her mat at the hair salon

Straight up desensitization without any bells and whistles is my favourite way to teach a settle, but if you’re dealing with hyperarousal or an extinction burst, it may not work for you. If you have a brand new puppy, desensitization training should be part of your daily socialisation practices.

Here’s how you do it.

Step One. Identify a situation where your dog can settle.

For puppies, I advise starting your practice when they’re sleepy. Puppies tend to operate on an eat->sleep->rave->repeat cycle, so just catch them when they are swinging back around to nap time. For adult dogs, choose a time of day and location (usually at home, perhaps after a walk) when they typically nap. For this step, be present with your dog such that you won’t trigger any separation related behaviour. Even if you think your dog can’t settle anywhere, they do have to sleep sometime. There is always a place to start.

Step Two. Build your environmental cues.

I use a towel, mat or blanket. Having the leash on gives me the option to tether, if needed, so you might want to always practice on leash as well. Once the towel comes out, my dogs recognize that we are entering a settle scenario through sheer routine practice. Make sure that you initiate the settle the same way each time, so that your environmental cue can be well-understood. You can use a different set of environmental cues, like a car crate or a gated area, but the concept is the same. Later, we will leverage these environmental cues to signal a settle in an otherwise less obvious settle scenario.

Step Three. Practice.

In your settle location, bring out your towel and guide your dog onto it without the use of food or toy rewards. Since your dog is primed to settle anyway (see step one), it shouldn’t be too hard to encourage them. If they get up at all, just gently guide them back to the towel or mat. Let your dog nap for 10-30 minutes, then guide them off the towel and put it away. You need to do this most days, as repetition is what forms habits and the key to success here is forming a habit. This step should feel like cheating. It’s OK to feel like you aren’t really teaching anything, because you’re not. You’re leveraging a natural behaviour that was going to happen anyway, and adding your environment cues. Run with it.

Step Four. Change one thing, then Practice.

Now for the desensitisation part. You want to keep the napping behaviour and the environmental cues the same, while changing the environment very slowly and methodically. Each week, change one small thing and practice until your dog can settle reliably with the change. I typically start by practicing in different places within my home, or adding some kind of motion or sound around them. Once that’s reliable, practice at the same time of day in a familiar location - I like my local greenspace, vet reception or starbucks patio. I might change the time of day in following weeks, and then incorporate less familiar environments. Finally, the very last step to tackle is settling your dog when they don’t really want to settle; maybe before their morning walk when they are full of beans, rather than afterwards when they are tired.

The first few attempts in a new space, at a new time or with some bigger feelings might look messy, you might need to guide your dog back to the mat a lot. That’s OK. As you practice, the routine of settling should solidify and when the mat comes out, the dog should start thinking “nap time”.

How to train a settle method 2: dESENSITISATION AND pACIFIER

14 week old Eleanor at the hair salon. She is napping on her mat with a pacifer (chew) under one elbow.

This method is for everybody who read the last method and thought “I am absolutely not doing that”. In defense of method 1, people do it by accident all the time. Next time you see a chilled out shop dog, or a pub dog or a dog relaxing at a campsite ask the owner how it was trained. I guarantee they’ll say something along the lines of “well… they’re just used to being here, I guess. We do this a lot”. If Steve from down the road can settle his dog by accident through desensitization and habit-forming, then I believe you can do it intentionally.

In defense of method 2 well, who doesn’t like a short-cut? We use this short cut in group-classes, and it works beautifully.

Method 1 makes the rather bold assumption that your dog wants to settle. In fact, the hardest part of the process is practicing at the right time to capture that nice natural settle behaviour. If your dog is excited already (for example, in a group class setting), if there are lots of distractions around (group class) or, if you haven’t got much control over the location and time for practicing (group class) then something is going to give. Or, well, you are going to have to give something. In this case, we give the dog an edible pacifier which is effectively just some kind of long-lasting chew item or a lickable frozen food toy.

If you pass your dog a pacifier in this situation, it can help the dog:

Ignore distractions

Disengage with handler (reinforcement comes from the object, not from you)

Approximate a settle (lie down, relaxed body)

Repetitive licking / chewing actions can help some dogs actually settle and fall asleep

You might not get the full settle in this situation, but what you are getting is valuable time in the settle-scenario with something that’s a close-enough approximation for habit-building. If you can hang out and chew/lick for a while in a busy space, the busy space will become less novel, more familiar and less exciting. This allows you to slip back to method 1 (no pacifier) much more easily when the dog is comfortable with the environment.

Like any good shortcut, it can backfire. Edible pacifiers are very exciting for many dogs, so choosing the right pacifier can help reduce excitement while still serving it’s function. I try to avoid over-reliance on a pacifier, so my dog doesn’t expect it every time I bring out the settle mat. Think of it as a kind of “fast pass” to enhance your settle training in tricky places, not as the settle training itself.

How to train a settle method 3: Interval Schedules of Reinforcement

If you’ve painted yourself into a corner already with a dog who is oscillating between obedience stay and extinction frustration, then unfortunately the ship has sailed for easy desensitization. I won’t say you can’t do desensitization, but it’s going to be much tougher. Desensitization involves no reinforcement, so it can trigger extinction immediately especially if your dog is already clued in to the environmental cues that should be signaling a settle. It IS possible to work through this with desensitisation, if you have good patience and a strong understanding of splitting criteria. But switching gears back to reinforcement might actually make sense here.

The best way to remove reinforcement gradually from a settle scenario is to switch from a ratio schedule to an interval schedule of reinforcement, then build duration between intervals. This is some real behaviour-nerd stuff, so I need to break it down. Bear with me, or just straight up skip this part if your brain is switching off (it’s OK, I won’t judge).

There are 4 classic schedules of reinforcement as follows:

Fixed Ratio Schedule: The dog gets a treat after a predictable (fixed) number of successful repetitions. For example my dog might know he has to wave 3 times to earn a treat, so he always waves his paw 3 times.

Variable Ratio Schedule: The dog gets a treat after an unpredictable (variable) number of successful repetitions. For example my dog might know he has to wave a bunch of times before he earns a treat, but he doesn’t know exactly how many times. He will keep waving until the treat is given.

Fixed Interval Schedule: The dog gets a treat after a single successful repetition, after a fixed amount of time has passed. If my dog picks up or paws his food bowl, I will feed him. But I won’t feed him again until at least 4 hours has elapsed. Picking up or pawing his bowl when it’s not meal-time results in no reinforcement. Mealtimes are predictable, which makes this fixed-schedule.

Variable Interval Schedule: The dog gets a treat after a single successful repetition, after a variable amount of time has passed. If my dog picks up her leash or paws at the door, I will take her out. I won’t take her out again immediately after, but if she asks after some time has passed I might take her out again. My dog has no way of predicting how much time has to pass before the door-pawing behaviour will work again.

The first two schedules are the main ones we use when we train our dogs. Ratio schedules just make sense when you’re looking to reinforce specific behaviours. Do the behaviour(s), get a treat. Simple.

But settle isn’t a specific behaviour, or even a series of behaviours, it’s a state of mind. This actually makes interval schedules a little more appealing. Your dog still gets treats for offering stay behaviours, but they should start to realize that some time has to pass between receiving food and earning the next reinforcer. A fixed interval plan for settle might look like this:

Step One: Choose the reinforceable behaviour. For me, I like a down on a mat with the dog’s head resting on the ground.

Step Two: Choose the interval. I typically start with 10 seconds or so.

Step Three: Implementation. Wait for the dog to offer the behaviour, mark and reinforce. Count to 10 in your head (ignore all behaviours in this time). When 10 seconds is up, repeat this step from the beginning.

Step Four: Increase the interval over the course of several sessions, so the dog has to wait longer between feeding. If the dog moves away from the mat a lot between treats, then the interval is too long.

A variable schedule is even better, because it makes it harder for the dog to predict when the behaviour will work and when it won’t. This means that they are more likely to just keep offering the behaviour just in case, but it’s a little harder to keep track of variable intervals in our heads, so that’s the trade off.

Interval schedules help avert extinction by teaching the dog that there’s just always going to be some “dead time” built into the game. The interval itself can get bigger gradually, so the dog learns to tolerate more and more “dead time” where the handler is “disengaged” and not available to dispense food. Since the handler should be disengaged during a settle, interval schedules of reinforcement actually make sense to use here.

If you think this sounds complicated, then you’re correct. This is an unnecessarily complicated way to teach a settle, and I absolutely do not recommend it. The reason it’s in the blog is that firstly, it does actually work. I did this with Percy, after making the classic “settle-must-just-be-a-long-stay” mistake. Secondly, it’s one of the few times interval training schedules are actually relevant, and I’m just excited to get nerdy about them. Watch me never get to use an interval schedule for reinforcement ever again in my whole training career.

Make Reinforcement Less Exciting

If you have to use reinforcement, but you can’t be bothered for the schedules I was talking about above, then I have some hack methods for making reinforcement a little less ruinous to your settle training. You can pick and choose which tactics you include in your settle strategy, but I do recommend incorporating at least a few of these ideas.

Remote Reinforcement. Part of the issue with treats is that they come from us. If we are delivering reinforcement, we become part of the settle picture which can be detrimental if you’d actually like to ignore your dog for a while. Enter the remote feeder. These little gadgets can dispense food on a timer, or via a little remote button. This can get your dog to focus on the machine, instead of you. Your dog might start with an active stay-like interest in the remote feeder, but since they can’t influence it’s behaviour as they can with you, they should become bored more quickly and just settle and wait by the thing until it dispenses a treat. When used with Non-Contingent reinforcement (below) I think this can achieve the best settle behaviour for the least amount of effort from the handler (read: work smarter not harder people, this is for you). The two major brands of remote feeder are Pet Tutor and Treat ‘n Train.

Non-Contingent Reinforcement (NCR). NCR is giving your dog food regardless of the behaviour(s) they are doing. Instead of faffing around with schedules of reinforcement for specific behavior as described in method 3, you can always just throw treats at your dog at a rate of x treats per minute and gradually throw fewer treats as time goes on. As your dog isn’t doing any specific behaviours to earn the treats, they should start to learn that their behaviours don’t actually matter, and then they can just relax and wait for the next treat delivery. Most of our extinction-burst dogs are out here trying to trigger a treat toss by lying down, wiggling, sitting or moving on and off their mat, so de-coupling treats from contingent behaviour can actually help a great deal in this scenario. Just be careful to be truly non-contingent in your reinforcement - if you start biasing towards specific behaviours then you’ll find yourself back at square one. If using NCR make sure to always deliver the treat to the mat or settle area - this way, your dog will gravitate back to this area even if they have a tendency to move about in the beginning.

Non-Food, Non-Toy Reinforcement. Toys and food are both really exciting, but there are other nice things out there that are less exciting to our dogs. If your dog enjoys praise, scratching or stroking, then these can sometimes serve as reinforcement in place of food. Your mileage may vary, however as different dogs find different things reinforcing. Many dogs don’t like being pet at all.

Alternative Marker. I don’t use my clicker when training a settle, because the clicker is inherently exciting. This is because the clicker is inextricably linked with our fun, play- and food-filled training sessions. Since I am not looking for engagement during a settle, if I do need to mark and reinforce a specific behaviour I will use a verbal marker “good” instead of the click sound. The “Good” marker only happens during a settle and I try to make it as boring as possible. This way, I can avoid piquing my dog’s interest if I’d like them to continue to disengage.

Single-Rep Sessions. Single rep sessions do what they say on the tin. I might choose to mark and reinforce one single behaviour, and then go back to what I was doing with no more treats available for the dog. By practicing single-rep sessions throughout the day I can teach my dog that just because they earned one treat just now, doesn’t mean there are a whole lot more around the corner if they just try hard enough. This helps reduce their expectations after receiving food.

“All Done” Cue. Like single session reps, the “All Done” Cue is supposed to help the dog understand that there are no more treats to be had after a training session. By ending every training session with the cue “All Done!”, you can establish that this cue means treats are not available. Now, when your dog is demanding food during a settle session, you have a way to inform them that no food is available. This has to be done carefully, otherwise the all done cue can cause your dog serious frustration. When I use “All Done!” I end on a high note with a little treat scatter. While this is one I’ve used, I can’t say for certain if I think it’s helped tremendously. I do think that practicing frequent single-rep sessions is probably more advantageous overall for a food-pushy dog.

Capturing Calm Behaviours. I’ve spent a lot of time capturing various calm behaviors in an effort to improve settle training. These are usually body language behaviors which accompany a calm internal mental state, and the theory is that by capturing these specific behaviours our dogs will “fake it until they make it” into a state of calm. You can train your dog to take a deep breath, lie on their side, yawn or curl into a ball. It does work, but it’s also very hard to do correctly in my experience. To get this to work, you have to have impeccable timing and you have to tread the fine line between capturing the outward behaviour and nurturing the inward mental state.

Photo by Isaac Davis on Unsplash

My dog cannot settle: emotional state AND pATTERN gAMES

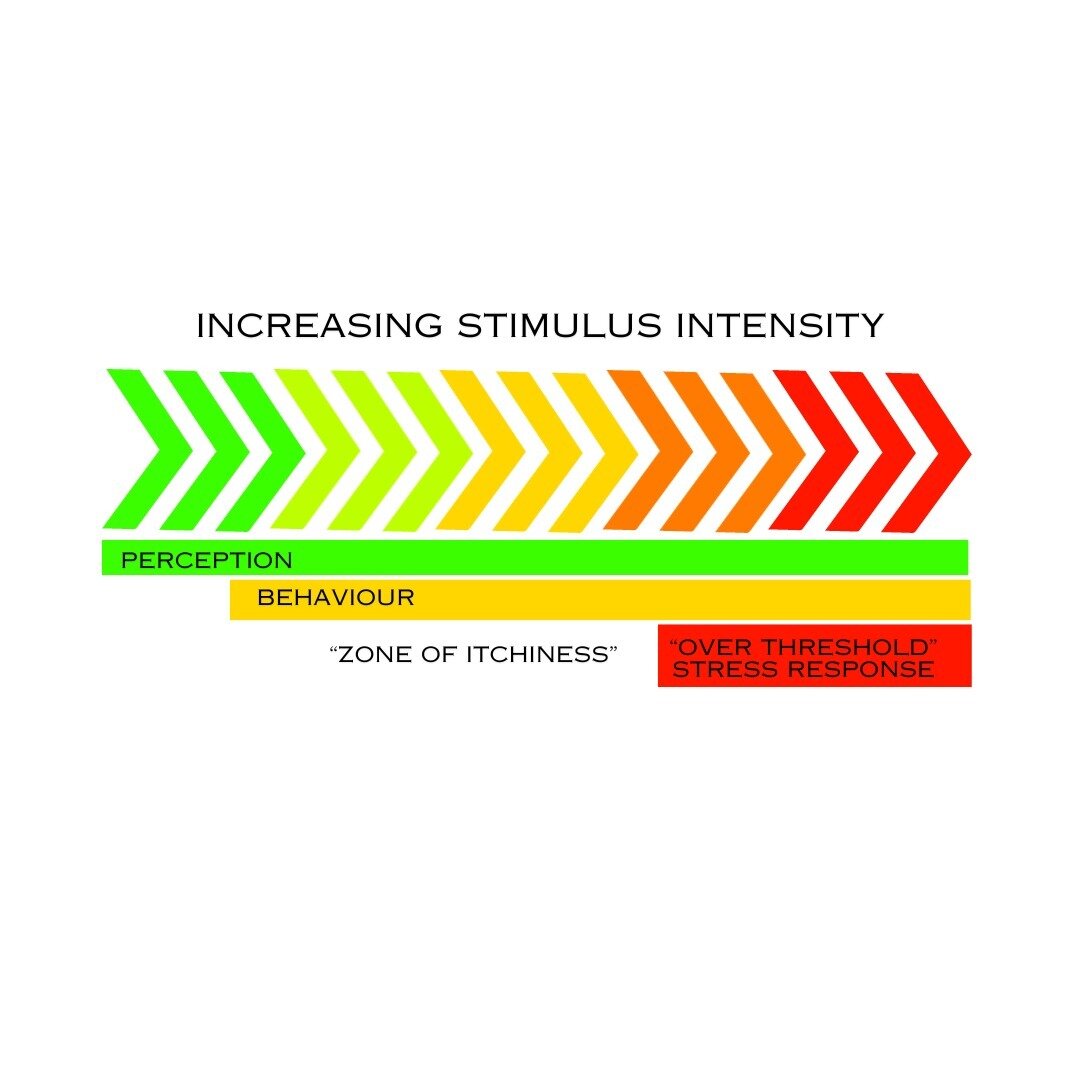

Sometimes dogs cannot settle due to hyperarousal, reactivity, hypervigilance or some other outward expression of an internal emotional state. When it comes to settling, it doesn’t really matter what kind of feelings your dog has. Any big feelings - fear, excitement, anxiety or so on - can completely derail your dog’s ability to settle. This isn’t because the settle training I’m describing doesn’t work, it’s because you my friend, have some bigger fish to fry.

All dogs have big feelings sometimes. It’s absolutely normal. It becomes problematic if your dog cannot relax even after implementing systematic desensitization to the environment or once your dog is struggling, they spiral out of control spectacularly. In both cases, you’re really looking at a larger behaviour modification plan which is a topic for another day… but we can’t really discuss settling without talking about pattern games.

The OG pattern game is Karen Overall’s Protocol for Relaxation, which is an absolute mammoth training protocol in the sense that many people have tried it and it also contains roughly a billion steps. You can download it here. If you read through the protocol, you will discover that it’s effectively a very well proofed down stay - exactly the type of protocol I told you not to do earlier. And yet, it’s given people tremendous success. So what’s going on?

When dogs have “Big Feelings” about an environment or a trigger giving them a repetitive, predictable task can be tremendously effective to help them work through those emotions and learn to self-regulate. My suspicion is that the KO protocol doesn’t actually teach settle, per se. What is does is help dogs build some impulse control and resiliency, leading to better emotional regulation overall. Then, with better emotional regulation, comes the ability to do straight up desensitization. In fact, if you read the second tier of the relaxation protocol program (which nobody ever does), it goes on to explain some desensitization and counter-conditioning steps.

Where the relaxation actually comes in, is that once a stay is so thoroughly and deeply conditioned as described in the protocol, it becomes quite boring for the dog and the dog slowly starts to move from a state of “actively working for treats” to a state of “passively waiting for treats”. It’s a subtle shift, but when it happens, suddenly you do actually have a settle. The main problem with this protocol is that it’s too tempting to skip steps when we think our dog has already mastered them. But skipping steps and pressing on actually breaks the protocol - the whole point is to make stay boring and repetitive, not to achieve the posted criteria quickly. The real success happens when you are able to read between the lines of the protocol and look for the emotional state change in the dog as the stay-proofing is progressing.

There is another, bigger, fatal flaw in this program and that is in the case where a dog is triggered into a state of hyperarousal by the presence of food. If food itself is a trigger, as it can be for many dogs (including my dog, Percy), then this protocol is just not for you.

The protocol for relaxation has a place in dog training lore, but it’s no longer something I actively recommend for most guardians. It’s just too cumbersome and easy to mess up. For behaviourally typical dogs and especially food-crazy dogs, the methods I describe above work better. For our Big Feelings Friends, newer and better pattern games have been developed which actually do more to build resiliency in our dogs. For these games, read Leslie McDevitts “Control Unleashed” and keep your eyes out for signs of emotional state change, not just successful repetitions of target behaviours.

How we got here, and how to move on

Settle is more about training a relaxed mental state than an outward body posture. When we try to train a specific behaviour with food, we often nudge the dog into an excited emotional state, which is counter productive to the original goal.

It seems obvious in hindsight that food can cause issues in settle training, but how we got here makes complete sense if you know the historical context. Old-fashioned dog training techniques called for simply punishing the dog for moving, whether it was from a stay or a settle. Dogs of the past quickly learned to comply to avoid unpleasant punishment, and then figured out from context whether they were supposed to wait for a release cue or not. Since neither stay or settle had any expectation of reinforcement, only punishment, the dog never became outwardly frustrated when the expected release cue didn’t come. Trainers from this era trained long- and short- duration stays, and applied them to settle scenarios with minimal issues. Thankfully, we’ve collectively moved on (most of us, anyway) from punishment based stay training but in modernizing these protocols with direct “punishment” to “reinforcement” translations, we created new problems which remain largely unsolved for those not in-the-know.

The Karen Overall Protocol for Relaxation is a prime example. When this was published in the 90s, we were still largely operating under the general assumption that a settle was just a very long, very boring stay. If people were noticing that their dogs were fidgeting more and prone to extinction bursts, well, we could just add more steps, split more training criteria and make stay so boring that eventually we’d get to where we wanted to go. Clicker trainers are kind of intense like that - if a protocol isn’t working we will just add more steps. Tinier steps. It usually works, too.

I wasn’t around for dog training 20-40 years ago, but I get the impression that the average pet people only really sought training solutions when they were struggling, and that the positive-reinforcement based protocols were really only wheeled out in emergencies. These days pet parents are training their dogs by default, not just because they need some immediate damage control. This is a big win for dog welfare, but when it came to teaching settle we kept reaching for the Hail Mary solution, because it was all we really had.

Luckily for all of us, dog nerds everywhere are re-discovering and documenting the methods that actually work and adding them to the body of resources other dog nerds and pet parents can collectively draw from. I hope I’ve done that here, and that you’ve come away from this article with a few more tools in your toolkit.

As always, I appreciate feedback, discussions and sharing this content. Please don’t hesitate to leave a comment or ask a question.